Making Vinyl 2023: a view from the plating bath

Martin Frings

30 September 2023

Making Vinyl asked us to do a short session at their recent conference in Haarlem – on how the record industry looks from the perspective of a galvanics company. Here’s an edited version of the talk…

What trends do we see from our production stats?

Run lengths are creeping up. if we compare our production data for 2022/23 to four or five years ago, we can see a big increase in the percentage of orders that are 2-step compared to 1-step, plus a lot more orders for additional stampers.

A lot of our pressing plant customers, having established themselves in the market, are now getting longer-run orders from some of the larger independent labels. And anecdotally, it seems that a typical small independent band that may have considered pressing 300 records in 2019 … now might be ordering 500 –1000.

There has been a significant worldwide increase in pressing capacity – particularly in North and Central America. (For Stamper Discs, only around 20% of our orders are from UK customers, with around 60% from Europe, and 20% from the rest of the world.)

Which means – as everyone is aware – an increasingly competitive market.

There is potential for growth of Direct Metal Mastering (DMM) beyond the major plants. In an attempt to avoid almost total dependence on a sole lacquer manufacturer, some engineers have begun to retro-fit Neumann lacquer lathes to cut DMMs.

There are a handful of European suppliers comfortably meeting demand for blank DMM disc supply at the moment. Expansion of this capacity wouldn’t require significant time or investment should more DMM lathes come online.

We are also seeing many of our customers adding manual presses so that splatter records become an increasingly large part of many pressing plants catalogue.

Lastly – and sadly – we are noticing a small decrease in 7” orders, with many plants choosing to streamline their process to 12”

What challenges does the galvanics sector face?

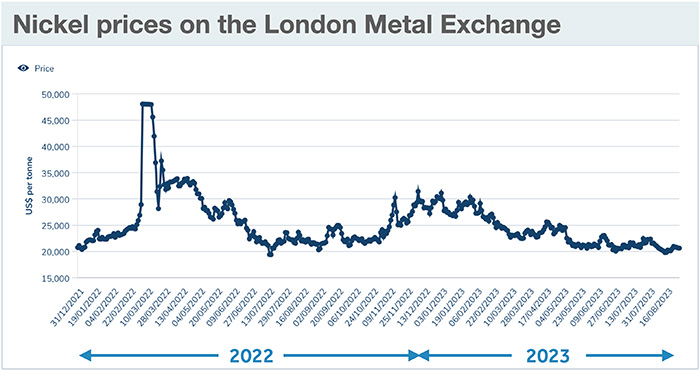

The volatility of the nickel market is rarely mentioned when people talk about the challenges facing the record industry. Stampers are made of electroformed nickel, and the price of nickel fluctuates on a daily basis, based on trading at the London Metal Exchange (LME). Although the LME nickel market has been more stable recently, in March 2022 there was a spike where the prices roses by 250% in a single day.

This was caused by a Chinese billionaire who controls most nickel mining in the Far East nicknamed ‘Big Shot’. He was betting that prices would drop when some of his new mines came online in the next year. But the traders saw prices rising due to the war in Ukraine and started betting against him… He was then looking at a $10 billion loss as prices rose. Luckily for him, LME then shut down the entire market, and he got off the hook…

But this meant that – for a period – nickel was unavailable, because no-one could trade without the LME market. The effect this had was so severe – at a time of huge pressing backlogs – that at least one large plant simply stopped taking new orders until the market stabilised and they were able to buy nickel again. Measures have now been put in place to stabilise the market and hopefully avoid another such incident, but it exposed a volatility in the market that is not often talked about.

Another challenge within the galvanics production area is chemicals and health and safety. Some of the chemicals used to make a stamper have to be handled extremely carefully – and the regulations on what can be used are getting tighter

The most notable examples this year have been Potassium and Sodium Dichromate, which are often used to ‘passivate’ the surface of a mother before a stamper is grown from it. These chemicals have now been listed as Substances Of Very High Concern requiring authorisation before use. Whilst some plants such as Stamper Discs have long used electrolytic or non-toxic alternatives, many plants have had to very quickly adapt their processes to stop using dichromates to passivate.

The most notable examples this year have been Potassium and Sodium Dichromate, which are often used to ‘passivate’ the surface of a mother before a stamper is grown from it. These chemicals have now been listed as Substances Of Very High Concern requiring authorisation before use. Whilst some plants such as Stamper Discs have long used electrolytic or non-toxic alternatives, many plants have had to very quickly adapt their processes to stop using dichromates to passivate.

Some plants also use Chromium Trioxide to remove the silver from stampers. This is next in the firing line. One alternative approach to using Chromium-based strippers to ‘de-silver’ stampers is to use a very gaseous process which involves a reaction between ammonia and hydrogen peroxide. Whilst not being carcinogenic, this process is also unsafe and not suitable for a modern factory.

The EU is moving faster than the UK in regulating the use of these two chemicals. But there is one area that the UK is much tougher on than the EU, and that is exposure to nickel.

The EU is moving faster than the UK in regulating the use of these two chemicals. But there is one area that the UK is much tougher on than the EU, and that is exposure to nickel.

Nickel is in many everyday items from cutlery and hip replacements to stainless steel. It is also present in a wide range of foods such as nuts, chocolate and soybeans… But it is by no means inert and has its own associated health risks. This means biological monitoring of staff is essential when working with nickel to avoid any long term health risks.

Here in the UK, we conduct regular urine testing to ensure that our staff do not exceed the mandatory level of 24 micromoles of nickel (likely to drop to 14 in the near future). Someone never exposed to nickel would have a natural level of around 11 micromoles. But in the EU, the guidance limit is a massive 64….

How our customers – the ‘new wave’ pressing plants – are differentiating themselves

Whilst the larger plants seem to mainly compete on price per unit, the smaller new plants have to find other ways of differentiating themselves.

A hyper-local market. ‘New wave’ plants often get a large proportion of their orders by serving their local market. The main benefit of this to a band or a label is that they can do something as simple as going and picking their records up themselves in the knowledge that they are supporting a local company – not just sending money to a broker without even knowing which country their records are being pressed in. And there are also arguments around shipping costs and sustainability, that support this local market approach.

Cultural hubs. These same pressing plants also function as cultural hubs embedded in their local music scene – also offering everything from recording studios to coffee shops and bars, as well as pressing records.

Better turnaround and service. A small local pressing plant finds it much easier to offer a personal service. There’s a number you can call and someone who wants to help at the other end. Without the clunkiness of being a huge company that offers everything from USB sticks to books, the ‘new wave’ pressing plants are quick to adapt to ever changing demands. And if you need a pressing miracle we’ve seen everything from overnight turnarounds to getting a test pressing to someone on their death bed.

Quality, quality, quality. It’s hard to make an exceptional product if you don’t care about what you’re making. What is ‘within tolerances’ on a dance record is unlistenable on an ambient soundscape and you need someone who understands that important distinction.

Supporting local bands and artists. Many plants actively support bands with promotions, compilations and even annual competitions giving unsigned bands free pressings. And in turn, independent artists recognise that supporting a local pressing plant pays back in the long run.

These are some of the ways we’ve seen our customers differentiate themselves, and to avoid boiling everything down to price.

But speaking of price…

The growing gap between production costs and retail prices for vinyl

I think the biggest long-term threat to the record industry is extortionate retail prices.

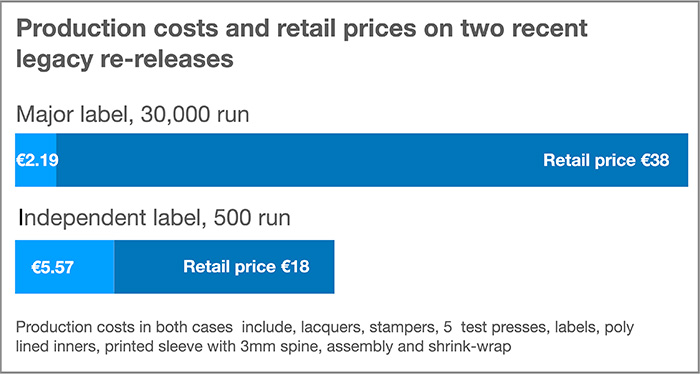

Here’s a real world price for a run of 30,000 records: unit cost €2.19. That includes everything from lacquers to test pressing to printing to labels, to sleeves, to shrinkwrap.

It retailed for €38.

For comparison, another real world job, this time an independent release. 500 records, unit cost €5.57.

It retailed for €18.

Both of these are for reissues of legacy material – meaning that there are very limited costs associated with studio time or marketing.

A retail price of €38 is unaffordable for many music fans and is impossible to justify. This price gouging by the major labels is blinkered and stupid – because it will alienate the new generation of record buyers we need to sustain the industry in the long-term.

How the climate emergency might change how our industry operates

The climate emergency means that reducing the carbon footprint of the record industry is rising to the top of everyone’s agenda. There has been a lot of excitement around advances in PVC manufacturing as a way of reducing carbon emissions – but shipping costs can also be a major component of a record’s carbon footprint, and one that is often overlooked.

We recently heard about a pressing plant in Northern Europe shipping a very large order to Australia by air freight.

Whilst nobody has done a proper carbon footprint of a vinyl record yet*, the figure is likely to in the vicinity of 1kg CO2e emissions per record. This is a ‘cradle-to-gate’ estimate covering the lifecycle up until the point the records leave the pressing plant.

We do have audited figures for the impact of shipping goods by air freight. And for every 1000 records shipped in this scenario – as opposed to being produced locally – the air freight adds another 4 tonnes of CO2e to the production supply chain…

That’s 4kg CO2e per record… which means that the carbon footprint has quadrupled – just by not being manufactured locally. (Australia is served by 3, and soon to be 4, pressing plants.)

So I think we’ll find that the biggest and easiest thing anyone can do to reduce carbon emissions is to avoid any air freight and manufacture locally.

From the map of pressing plants around the world curated by Making Vinyl, you can see that unless you’re pressing records for Greenland, there’s a very high chance you’re not too far from a pressing plant. Especially with new plants coming online next year with an aim to support the Middle Eastern, North African and Indian markets.

The climate emergency means labels and artists must begin to think differently about their supply chains.

The message has to be ‘Think Global, Press Local’

*Stamper Discs is working with the VRMA and the Vinyl Alliance on a project to understand the carbon footprint of a vinyl record from cradle to grave. We’ve completed our own carbon footprinting of the stampers we manufacture