The physical attributes of a stamper – eccentricity

Martin Frings

10 October 2025

Of all of the issues in the manufacturing chain that can affect a finished vinyl record, an off-centre record is perhaps one of the most easily identifiable by the end customer.

Yet there’s a lot of confusion on acceptable levels of eccentricity, both historically and in the present day. A 19691 article commissioned by the Journal Of Audio Engineering studied over 100 pressed records both in the US and Europe and found it was the one specification that the record industry routinely failed to meet.

So what is eccentricity and how is it measured?

Eccentricity is how “off-centre” a record is. “Off-centre” means that the hole in the centre of the record is not concentric with the grooves on the record. This is visually identifiable during playback by watching the tonearm drift from side to side.

If a record is off-centre this causes the playback stylus to travel at different speeds, relative to the speed at which the record was cut, as the diameter increases and decreases. This results in a ‘wowing’ sound which distorts the audio, and is most prevalent on sustained notes. Pianos are notorious for their ability to highlight even a small amount of eccentricity on a vinyl record.

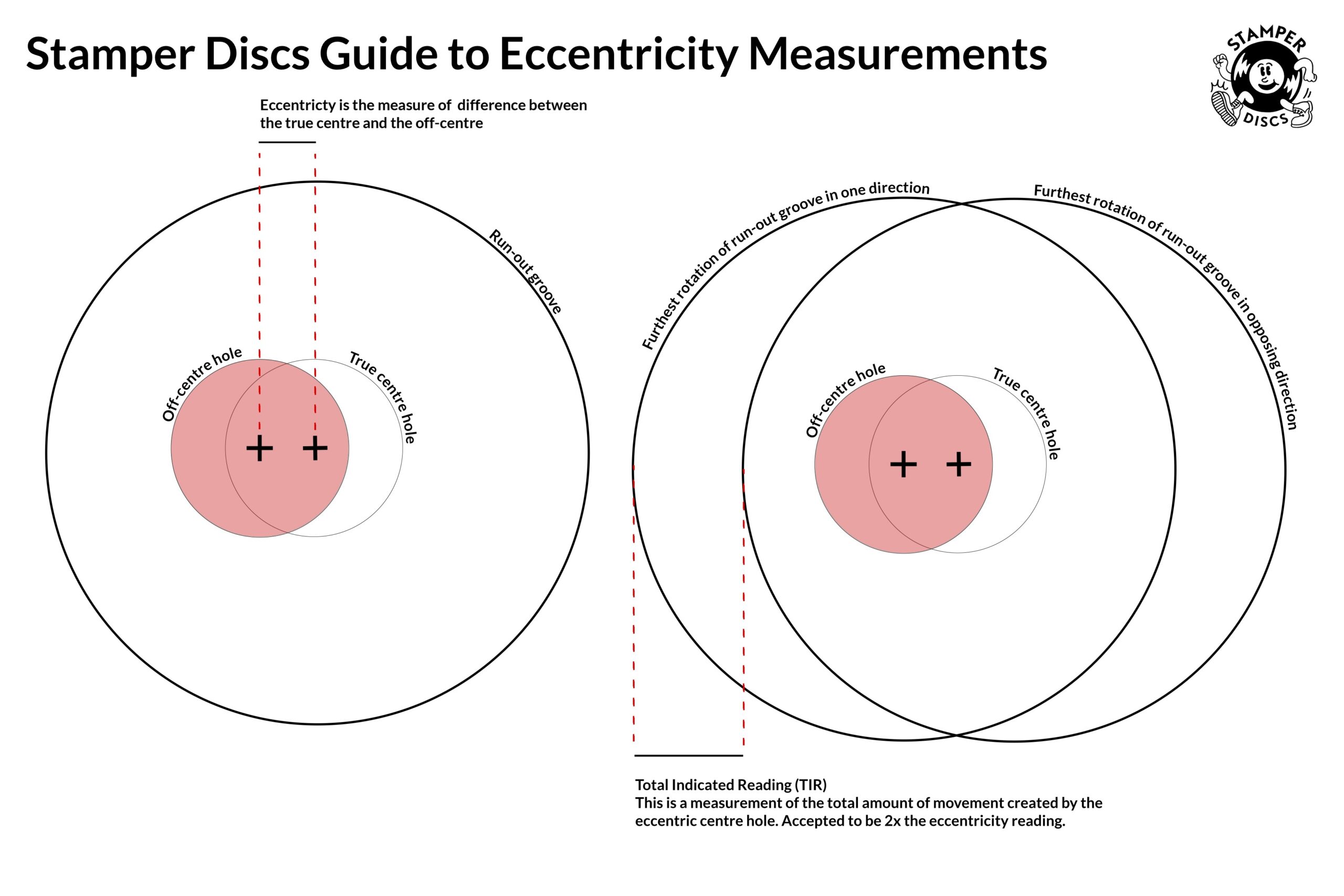

The diagram below shows the two different types of readings we’ll be talking about in this article.

- Eccentricity: the measure of how far off-centre the centre hole is. Expressed in engineering terms, “the degree to which two forms fail to share a common centre”. (In this instance the two forms being the spindle hole at the centre of the record and the grooves containing the audio.)

- TIR (Total Indicated Reading): a measure of the total amount of movement caused by the eccentricity.

In both instances in this article we’ll be talking in terms of microns (1000 microns = 1 millimetre). To give some context, a human hair is around 75 microns thick.

What causes eccentricity in a record?

The two biggest factors that can cause eccentricity are the centring stage during stamper production and when mounting the stamper on the press.

Centring – when a blank lacquer is cut on a cutting lathe the grooves are concentric to the centre hole on the lacquer. The lacquer is supplied with the hole already punched into it and thus the subsequent cutting is concentric relative to it – even if the hole itself is not perfectly concentric to the outer diameter of the disc.

A 1965 patent by RCA2 for an Off-Centre Indicator described the centre hole as being ‘obliterated’ during the stamper production process. Whilst ‘obliterated’ is a strong word for what is a relatively delicate process, it is true that the original centre hole on the lacquer is no longer useable as a reference point for concentricity.

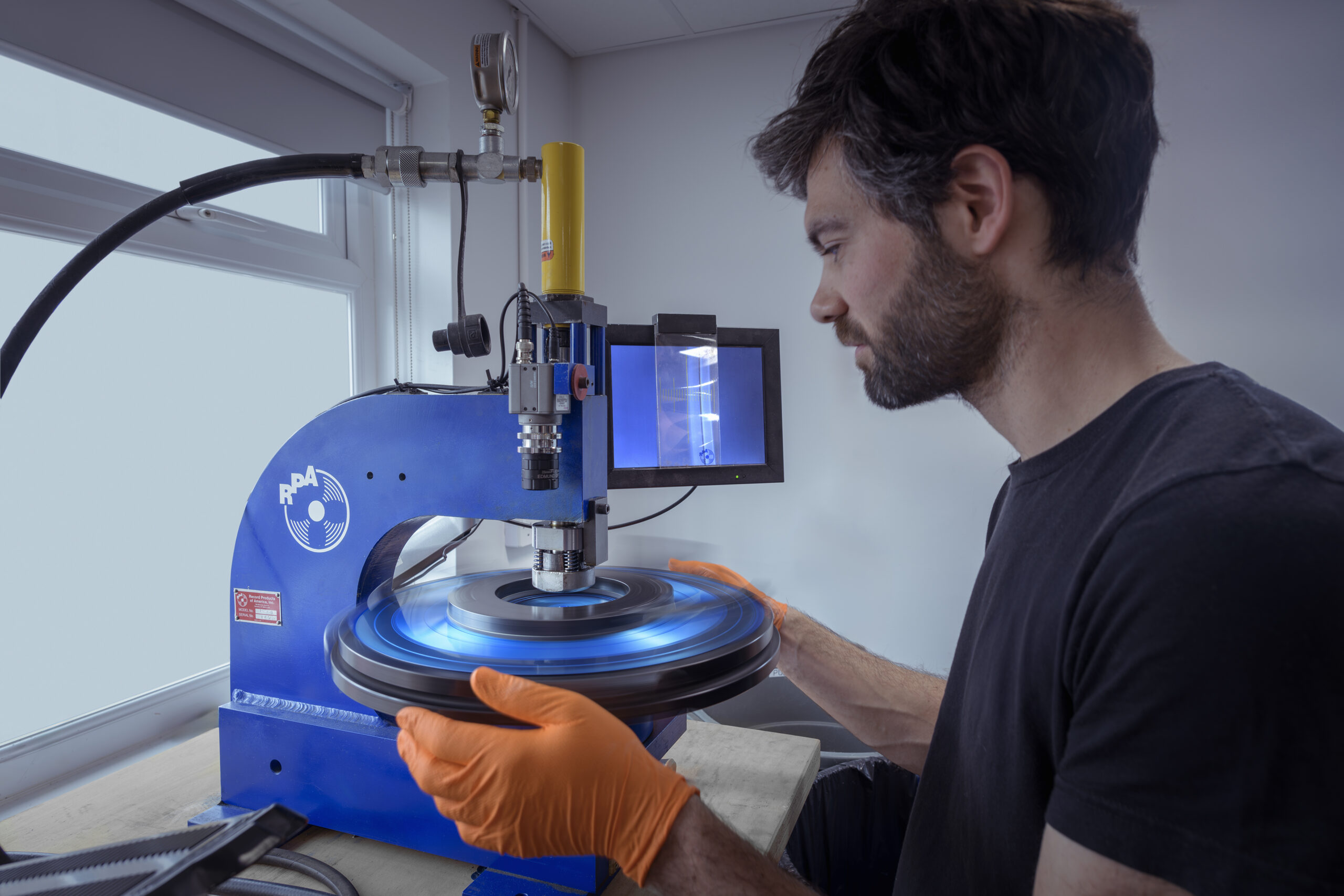

This means that prior to the stamper being formed to fit onto the pressing mould a new centre hole must be punched. This is traditionally done using a microscope mounted over the locked groove at the end of the record and adjusting it by eye until the operator deems it is suitably concentric. The accuracy of this operation relies heavily on both the skill/discretion of the operator as well as the level of magnification.

Under normal circumstances, creating the new centre hole will have the largest impact on the concentricity of the pressed record. Mounting – A secondary cause of eccentricity can be from the mounting of a stamper onto the mould in the record press. If the A-side stamper – mounted upside down into the mould – is not held securely in place by the operator whilst the centre bushing is being tightened, then a small amount of movement is introduced. The centre bushing is then tightened on this new eccentric placement and by doing this the centre is reformed. You can see below an example of this.

Mounting – A secondary cause of eccentricity can be from the mounting of a stamper onto the mould in the record press. If the A-side stamper – mounted upside down into the mould – is not held securely in place by the operator whilst the centre bushing is being tightened, then a small amount of movement is introduced. The centre bushing is then tightened on this new eccentric placement and by doing this the centre is reformed. You can see below an example of this.

Other factors – Although centring and mounting of the stamper are the major causes of eccentricity in the finished record, there are a range of other factors that can have a smaller impact.

These can include:

- Poor quality forming tooling.

- Poor trimming on a circle shears or the forming tool that pulls at the outer diameter of the stamper.

- Stampers too thin/thick meaning they do not fit the mould correctly.

- Worn moulds or centre bushing on the record press that allow a degree of movement.

- Incorrect process settings that ‘drag’ the stampers in the moulds.

- Misaligned moulds or even misaligned centre pins.

Finally, remember that the majority of record players have a degree of eccentricity in their turntables, and a centre hole that allows for some degree of movement around the spindle.

If each of the factors listed above contributed an imperceptible 5 microns of eccentricity that could potentially add around 50 microns of eccentricity (or 100 microns TIR) to an otherwise well-centred and pressed record.

What’s acceptable on a record?

Most businesses in the present-day record industry adhere (even if informally) to the 1963 RIAA Standards. These state that a pressed record should be under a 1.27mm (0.05”) degree of eccentricity. A follow-up bulletin also published by the RIAA stated that this figure does not imply this degree of eccentricity would be acceptable from a quality standpoint, simply that it would be deemed playable.

The 1964 ‘Recording and Reproducing Standards’ published by the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) stated that a radically more refined 127 microns (0.005” or 0.127mm)) should be the standard – 10x more concentric than that of the RIAA!

International (DIN45547-1981) European (IEC98-1958, IEC98-1964*2, IEC98-1987) and Japanese (JIS S8502-1973) standards all set the bar unanimously at 200 microns (0.008” or 0.2mm) whilst the British (BS1928-195) agreed with the NAB standard of 127 microns.

Optical disc standards raise the bar even higher with CD, DVD and BluRay discs being set respectively at 20 microns, 10 microns and 5 microns.

It could be argued that getting close to optical disc standards should be the goal for the vinyl record manufacturing world. Unfortunately these standards (with the exception of CD) are unrealistic for vinyl record manufacturing – but they do serve as a useful reference point.

One reason that optical disc standards are impractical for vinyl is because of the nuances of the record cutting process. When the cutting engineer is producing a locked groove at the end of the record to finish off the cutting spiral, they normally allow for a quarter rotation of ‘overlap’ as a safety measure to ensure the groove is fully closed. This overlap where the cutting spiral joins the locked groove can result in a groove width variation of around 10 microns. Because of this, it is not impossible to measure vinyl record eccentricity <10microns but it is impractical.

What do different amounts of eccentricity look and sound like?

Being told that a record has an eccentricity of 127 microns doesn’t help in understanding what that looks and sounds like.

We’ve produced the video below to try and help readers better understand how these issues present themselves in real life. Using a Filar Micrometer attached to a microscope over a turntable that allows us to accurately measure degrees of eccentricity, we have created a video to serve as an audio and visual reference video for vinyl record playback eccentricity.

A huge thanks to T-Time Vinyl Plant in Stavanger, Norway and artist Anette Askvik for permission to use her music.

Conclusion

Based on the more recent standards, and the evidence of what is practically achievable, we believe the record industry should always aim for an eccentricity reading of < 100microns – although < 200microns may prove acceptable depending on the characteristics of the music involved.

These figures relate to the playback of the finished record. This means that as a stamper supplier we must take into account the further amount of eccentricity that may be introduced by the pressing process as well as the playback process. For this reason we will always aim to produce stampers with a level of eccentricity of < 50microns.

1 John, Eargle. 1969. Review of Performance Characteristics of the Commercial Stereo Disc. Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 17 (4).

2 C Moyer, R. (1961). Off-center indicator (Patent No. US3000005A). United States.